oops

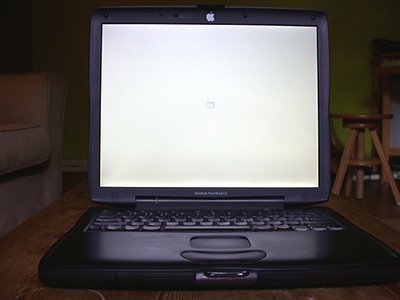

mac users call this the grey screen of death - the mac equivalent of the windows blue ditto: that blank folder in the middle is the hard drive saying "sorry but I can't find anything to boot myself up with - nice knowing you, goodbye, and thanks for all the fish."

which is a bit of a bummer.

so, five days later, and a few pounds (£) lighter, all's more or less back to where it was before the crash, and I'm left wondering how it is that this thing - this machine - this typewriter-cum-telephone-cum-television - has come so to dominate my - and your - and most of our lives. for, really, although I was striving, throughout those few days, to occupy my zen-detached place, and to persuade myself that the effective loss of a shocking amount of un-backed-up work was something that I could live with, I really wasn't fooling anyone, let alone myself, and the phrase 'on tenterhooks' came to reveal its quintessential meaning in the manner of my increasingly frenzied squirming on this wretched spike of insecurity the longer the uncertainty continued.

in so far as our sense of selfhood is largely a function of that pesky two-way mirror of perception - how we perceive that we are being perceived - the personal computer (particularly in its form as an interface with the internet and the world wide web) has become either a personality prosthesis or synthetic augmentation depending on how you look at it.

there can't be many people now under the age of twenty-five whose social lives haven't been as entirely circumscribed by e-mail, msn, blogger and myspace as their academic or working lives by Word, excel, and powerpoint (and/or photoshop, cubase, protools, dreamweaver, whatever ... ad-diddly-infinitum), and who regard the pc or mac - either in its desktop or laptop form (or, increasingly, in its mobile phone form) as an absolutely indispensable feature of their lives. the prospect of loss, then, is something that goes way beyond a previous generation's fears of losing their filofax - the loss of data is only a part of what is implied in the prospect of self-erasure faced by those standing staring into the lost-computer abyss. from choice of desktop image to preferred browser to lists of favourites to iTunes playlists, our personalities are embedded in our computers far more deeply than in the way we dress or in our choice of transport, and the potential loss of the machine reverberates deep in our neocortex as something akin to a cross between a partial lobotomy and the death of a very close friend.

this is no more something to be deplored than was the microphone usurping the megaphone, or the calculator usurping the slide-rule: it's the culture optimising the technology, nothing more, nothing less, and, by and large, the dystopian potential - for big brother-like social control, or exploitative naughtinesses of the phishing and scamming kind - is far outweighed by the potential for informed vigilance afforded by internet access.

it is, however, fairly alarming that the sort of nervous breakdown once forewarned by months or years of increasing individual dysfunction and announced by the gradual whittling-away of self-esteem by dint of the diurnal drip of corrosive human intercourse onto the fragile carapace of our tender personalities is now something that can happen in the few moments it takes between pressing the startup button and nothing happening.