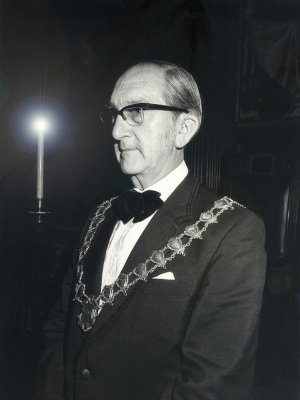

Leslie Walter Roylance 22nd May 1916 - 15th March 2006

As you probably know, Dad was born in Gorton, in east Manchester, in May 1916. He was the eldest of four, having two younger brothers and a sister. Sadly, Godfrey and Raymond predeceased him, although his sister, Molly, who caused something of a stir in the family when she married a missionary and sailed off to Papua New Guinea, is still very much alive and kicking down in Australia, and has just announced that she's planning a visit this summer.

When Dad was born, a mere eight years had elapsed since the first man-powered flight by Wilbur Wright at Kittyhawk. Claude Monet was painting his famous 'Water Lilies' and cementing the reputation of the Impressionists in art history forever, and the composer Gustav Holst was completing his suite, 'The Planets'. Overshadowing everything at that time, of course, was the terrible conflict of the First World War, with the Battle of the Somme only two months away, although the poets Wilfrid Owen and Siegfried Sassoon were forging a famous friendship on the Western Front, and writing the poems which were possibly the only good things to arise from that conflict, and Lawrence of Arabia was charging about on a camel meeting Omar Shariff on the Mesopotamian Front.

Dad was an almost exact contemporary of Len Hutton, a cricketing hero not only of his but of mine as well. He also very nearly shared a birthday with Gregory Peck, Olivia de Havilland, Kirk Douglas, Betty Grable, Yehudi Menuhin, Margaret Lockwood, and Roald Dahl, although if any of these people had anything at all in common apart from a coincidence of birth, I've failed to identify it. Perhaps they all liked ice-cream and mum's strawberry trifle, too.

I have very clear memories of that house in Oakfield Grove where Dad was born and brought up. It was at the bottom of a sloping Victorian terrace and on the edge of a park. Dad's upbringing was obviously strict but generous: my grandmother was a shadowy intimidating matriarch who smelt of mothballs - she died when I was seven or eight. But I used occasionally to call in at Grandad's on my way home from school. We played dominoes and I was allowed to light his cigarettes. He smoked Park Drive and occasionally Capstan, I think, and also had a Rizla rolling machine that I assumed worked by magic. I bought a copy of Roget's Thesaurus with the book-token he gave me on my thirteenth birthday, two months before he died. I still use it.

During my early childhood, Dad was a lay preacher at the local Baptist Church. I found nothing exceptional about this - I assumed, as children do, that that was what Dads did on Sundays, just as they played cricket and mended bikes on Saturdays and went to work during the week, and it wasn't until years later that I realised how exceptional this was amongst Dads, and furthermore, what a fine writer he was and a truly inspiring speaker.

This talent came to a late and glorious secular flowering when, after retiring from the bank, he embarked on a further career as a sometime lecturer, giving talks on his speciality of probate law. Although he finally had to give that up a few years ago as his failing sight prevented him from driving, I know that he got great pleasure from giving those talks, sharing the benefits of his experience with large numbers of people up and down the country. He was as witty as he was erudite, succeeding in making a talk about the amendments to the Inheritance Act of 1938 and the Law of Comorientes seem as much fun as an evening in with Morecambe and Wise.

There's no law, fortunately, that says fathers have to be repositories of homespun wisdom and advice. I say fortunately, because, if there were, I'd be a major transgressor. Either that, or I've inherited, as well as a host of fairly useful things like knowing instinctively how to reverse park and change a plug, the supremely sensible instinct as to when to hold your tongue. This might not be true for Nigel and Yvonne, but it was certainly the case for me - Dad recognised very early on that if he were to try giving me advice, I'd more than likely do the exact opposite out of sheer bloody-mindedness. So I don't, as some people seem to do, have many memories of his ever actually advising me to do anything.

Apart from the business of the little-known Denton West End Primary School playground wars of '54 - I was seven - when he took me aside one evening - he must have got wind of something going on - and said to me that if - he stressed the 'if' , because this was coming from one of the most pacific men I've ever met - if I were ever to find myself needing to fight someone, I should always remember one thing. My breath was truly bated. I assumed he was about to initiate me into some arcane martial arts secret that would have my enemy, David Winston, begging for mercy within seconds of my applying it. It was all about a girl, of course. Susan Haggas, of fond memory. If, he said, this were ever to happen, just remember one thing: don't keep your thumbs on the inside of your fists.

Which, if you think about it, is probably the most useless piece of advice any father ever gave to a son. I mean, what's that about?

Anyway, in the resultant melée, not only did I get my nose bloodied, but I got so confused that I almost dislocated both of my thumbs. Total triumph of David Winston. Except that, to the utter confusion of both of us, I got the girl. But that's women for you.

Tne only other piece of advice I can remember him giving was fairly obvious really, coming from someone whose working life was bound up with untangling the terrible messes people leave to their successors by dying intestate. Almost as soon as I was old enough to sign a legal document , he advised me to make a will. Sound advice. And, to give credit where credit's due, he's been banging on about it ever since. Have you made a will yet? Not yet, Dad. You ought to, you know. I know, Dad, you've been telling me that since 1968. So when are you going to?

Soon.

Alright then.

Alright then.

You won't, will you?

I will, Dad.

Will you?

I will.

Tomorrow.

In common with most people of his generation, Dad's capabilities extended into areas that would put most of my generation to shame: to us, multi-tasking is just a computer buzzword - Dad embodied it.

His career had made him an expert in probate law, although he was well-versed in general legal principles from the solicitor's apprenticeship he had undertaken before deciding to enter the world of banking.

Aside from the expertise he brought to his work, however, he was more than capable, it seemed, of undertaking any of the practical tasks associated with running a household: from concrete-laying to shoe-mending, furniture-repairs to glazing, he seemed to be able to put his hand to anything, as well as playing a mean organ, having a beautiful calligraphic hand, and playing a ruthless game of scrabble.

He was generous to a fault, infinitely patient, scrupulously honest, and unburdened, it seemed, with an ounce of selfishness beyond that required of individual autonomy: you'd almost have to hold a gun to his head in order to get him to admit that, yes, he really wouldn't mind if you offered him that last chocolate truffle.

As is often the case in families, most of my memories of him are connected with family events, and very happy memories they are indeed, but, quite recently, when I was visiting Manchester with one of my own sons, we were walking down Moseley Street so that I could show him the bank where his grandad had worked for most of his life, the Head Office of what used to be William Deacons, long-since metamorphosed into something else in that strange world of corporate evolution, and, as we passed those imposing entrance doors, I suddenly remembered a meal we had shared together, just the two of us, more than fifty years ago. For some reason I don't recall, Mum had dropped me off at the bank, and Dad had shown me around: I was completely overawed, of course, by what seemed to me to be a kind of palace - vast halls, echoing marble floors, dark wooden panelling, ornate light-fittings, and people talking in hushed whispers about very important things. I was introduced to some of his colleagues, and felt very proud to be associated with this man whose life here - quite separate from our home in Denton - had a whole set of meanings which were quite indecipherable to a child of eight or nine, but who was clearly liked and respected by a bewildering number of men and women who were complete strangers to me. Then he took me down to the staff canteen, and there we sat at a table, just the two of us, and ate lunch. I don't recall anything that was said. That wasn't important. I clearly recall what we ate, however: ox-tail soup, roast beef, carrots and mash with gravy, and apple pie and custard. And there we were, just the two of us, me and my Dad, and me glowing, my heart overflowing with pleasure and pride and love.

Parenting is a catalogue of firsts: first gurgle, first smile, first tooth, first step. What gradually creeps up on us as time passes, however, is a corresponding catalogue of lasts, most of which pass by unnoticed: the last broken night, the last nappy-change, the last piggy-back, the last bed-time story. And, little by little, the list of lasts inevitably begins to overtake the list of firsts, until, one day, there's this final set of last things to remember: the last time we ate together, the last time we shared a joke together, the last time we spoke, the last time we embraced.

The sorrow of Dad's passing is great, but I know that time will eventually heal that sorrow and replace it with an ongoing remembrance of his life, an exemplary life, full of kindness, generosity, and laughter, a life which, in the midst of our mourning, we should celebrate, with hearts overflowing with pleasure and pride and love.

No comments:

Post a Comment